No need to dream of a “Childhood in Another’s Hometown”, You Can Experience it Right Now!

Since the beginning of 2024, I have been volunteering for Stepping Stones’ programs, teaching English, digital literacy, and social-emotional learning. From teaching in Puxi to Pudong, the long weekly commute on weekends has become the work I look forward to the most. What touched me the most throughout this experience is teaching social-emotional learning.

What shape do your emotions take?

A blue and purple flower; a red and purple dragon with a green heart on a string; a long bracelet of red and bright yellow; bunny ears on a long, pink stick, a wreath of thorns…

In the social-emotional learning class, children gave us this answer with their own personal twist. The child which made the long bracelet explained it looked like an extra-large slide he had much fun playing on earlier; the child that created the wreath said it represented sadness, and that he was sad to discover there were some people who destroyed the oceans and polluted the environment for their own benefit. I’m amazed. Children under 10 already have such diverse ideas.

What are you most afraid of? Sticks!

Social-emotional learning (SEL) is a program that helps students of all ages to better understand their own thoughts and emotions, enhance self-awareness, and learn to empathize with others.

Most of my students come from the neighborhood of the teaching site. Their parents are laborers who moved to Shanghai; some work for chain restaurants, some work at the docks, and others run their own small businesses. With more and more moving into the city each day, more children are moving with them into a bigger, more unfamiliar world. Contrary to what one might believe, many migrant children do not come from poor families. Those who work part-time earn enough money to buy nice new clothes and Apple cell phones, and those who run businesses can even afford to hire a nanny.

But this dilemma is more complicated: the long hours required of manual labor make it impossible for most parents to take care of their children, and they usually must leave them in their homes. The lack of appropriate education makes scolding and disciplining common; children often have bruises on their bodies. In the first class, I asked the students what they were most afraid of. Many of them answered “wooden sticks”. Daily rough and cold communication can damage a child’s personality.

What’s more, the main aspect of this achievement-oriented theory also makes “doing homework”, which transcends many parts of daily life, become a burden on the hearts of some children: they learn to be “sensible” and “well-behaved” too early, and spend all their free time on confined to their desks.

The youngest student in our class is only in kindergarten while the oldest is already in fifth grade. The large age difference makes the classroom difficult to manage, but this is only the first hurdle. Our students include children who have trouble expressing themselves due to being confined to their homes for years, children who are nervous and cranky because their mothers are expecting a second child, and children who are extremely sensitive to touch and do not know how to communicate as a result of years of domestic violence.

Before stepping into the classroom, Teacher Yi from the teaching site, had already warned us about how difficult the class would be to manage. I thought, “There are only 10 of us, how difficult can it be?”

The Classroom: From Disarray to Order

After only one or two lessons, the rash mindset of the children immediately “hit us the face.” Most of the children were very active and had a very short attention span, making it almost impossible to keep them focused in a 70-minute class. From the beginning, the classroom faced a number of problems. Some kids sprawled across their desks to sleep, while others crawled underneath and lay on the floor. In the blink of an eye, minor squabbles between neighbors could escalate into shoving matches or full-blown fights, leaving one child in tears or both red-faced and refusing to back down. Even with two teachers managing the classroom at the same time, it was still very difficult to mediate conflicts and maintain order in the classroom, let alone actually teaching.

My partner, Ariel, and I took our time to figure out how to build a proper incentive system on top of the classroom rules (to listen, speak up, and respect others) that had been established by Miki, SEL program manager . Every week, we spent at least an hour discussing and preparing lessons to not only finalise the content, but also to ensure that every aspect of the class would be under control and meet our expectations.

For instance, some of the children already knew each other and had started playing together before class. Those familiar with one another tended to sit together and chatter during lessons, making classroom management even more difficult. To address this, we introduced a lottery system early on, where each child would draw a seat number. This randomised seating arrangement not only helped minimise excessive horseplay but also encouraged students to get to know different classmates during group activities. Since the assignments were random, even when some grumbled about wanting to “switch seats”, they quickly quieted down after we emphasized the absolute fairness of the system.

We observed that some children were excessively active while others were overly quiet. To motivate the quiet students to express themselves more and the talkative students to to listen respectfully, we implemented a reward system within the first few classes – positive responses earned points, while interrupting others resulted in deductions.

At first, we were all “soft-hearted” and not very strict in enforcing the rules. But gradually, we realised how keenly sensitive the children were to unfairness. If you praised one student’s contribution while overlooking another’s, or disciplined one child for a behavior but ignored the same action from others, they would immediately voice their protests – in a way, the students became my teachers, expertly pinpointing every inconsistency.

We also held ongoing discussions on how to improve. In November, I wrote in my notes after one class – Discussed how to award points to the kids during lessons. 1) Rules must be clear and standards objective; 2) Encouragement beyond the rules should be given in non-point forms. We established clear rules for everything – from seating arrangements and distribution of craft materials to classroom language and how to address tattling or violent speech – all to maintain a fair and transparent environment.

Establishing rules was relatively easy, the real challenge lay in handling classroom conflicts. Some children refused to team up with their neighbouring students, finding them annoying; others fixated on their scores, raising their hands constantly without genuine engagement. There were complaints about never being called on (“They stole my answer!”), accusations aimed at docking others’ points, and moments when a child, overwhelmed by emotions, simply shut down and rejected all rules.

With guidance from Miki, SEL program manager at Stepping Stones, we learned to prioritise emotional recognition in conflict resolution. When faced with a distressed child, we’d first gauge their “emotional granularity”, “On a scale of 1 to 10, how angry are you right now?” Then, we’d explore the cause – often, simply acknowledging their feelings (“I see you’re upset because…”) or facilitating an apology was enough to restore calm.

I discovered that children are far more open to reason during conflicts than adults, they don’t stubbornly cling to their positions. One moment they might be wailing uncontrollably, yet the very next second, if they sense your words are fair, they’ll instantly dry their tears and willingly offer or accept an apology. What often appears to be defiant chants of “I’m not listening!” usually masks an unspoken plea for their feelings to be acknowledged.

There was one telling incident where a child, in a fit of anger, threatened to tear up the lesson’s flash cards. When I gently said, “It would really hurt my feelings if you destroyed these.” He immediately stopped though still frustrated, he settled for dramatically tossing the card aside instead. That small act of defiance became his compromise, as if to say, “Fine, I won’t tear it, but I still need you to know I’m upset!”

By the middle and end of the semester, the classroom had miraculously quieted and we were able to control the pace of the class more comfortably, focusing more on teaching. We also saw some changes, eg. the boy who once dissolved into tears at minor frustrations now articulated his feelings and offered genuine apologies; the child who used to be self-centered and impulsive according to his mother, learned to pause and think before speaking at home; and the child who used to be seemingly indifferent to everything began to actively participate in the classroom and show his true feelings.

After each class, Ariel and I stayed for a while to talk to the children’s parents and Teacher Yi about our observations and to receive suggestions. On the way back to the subway station, we would share our observations and thoughts about the children’s behaviour during the class and gradually realise how to improve our teaching style. Every time we did so, we were excited about the new insights and discoveries we had made.

The most rewarding moments came when children realised classroom lessons held real meaning in their lives. After learning how to deal with anger, they began practicing deep breaths to self-calm during frustrating situations. When introduced to growth mindset, one child had an epiphany: “So I’ve been lacking a growth mindset all along!” The children began actively reflecting on their own and others’ behaviours – a developmental leap that truly amazed us. During our final class, one student’s self-assessment particularly struck me, “I feel scared to speak up, so I don’t share much.”

In one memorable lesson, we introduced the “Circle of Control” concept, teaching students to distinguish between what they can and cannot control in their lives. The discussion began predictably, with responses like “going to school” and “doing homework.” But soon, the conversation deepened in remarkable ways.

A student said, “You can’t control time because it moves on no matter what.”

I said, “Yeah, we can’t time travel.”

A few of the more resourceful kids pondered this. One child objected, and a soft-spoken boy slowly raised his hand: “Time is controllable! I can control what I choose to do with it.”

I responded, “That’s true!While we can’t control time itself, what we can control is how we use our time.”

Another usually quiet girl also raised her hand, “We can’t control growing up!”

The discussion didn’t reach a neat conclusion, and that was perfectly fine. What truly mattered was witnessing each child engage deeply with this personally relevant question, stretching beyond their usual thought patterns to discover the joy of intellectual exploration.

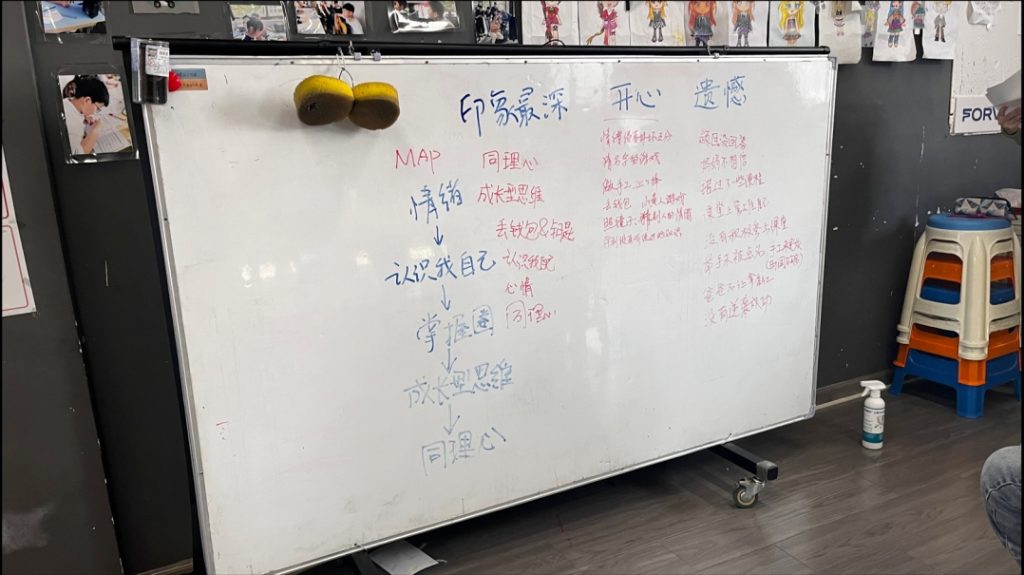

At the end of the semester, we asked the children to tell us what they remembered most from the class, what they were happiest about, and what they regretted. Some said the happiest thing was knowing that there are no good and bad emotions, and learning to accept their own “anger” and “sadness”; some said it was the most fun to play the game of looking into the mirror, so that they could guess other people’s emotions; some said the most regrettable thing was that they didn’t participate in class more actively; some said the most regrettable thing was that they didn’t “succeed against the odds” and get the first place in points.

On the final day of term, we asked the children to reflect on their most memorable, joyful, and regretful classroom moments. Their responses painted a vivid picture of growth:

“My biggest regret? Not making that epic comeback to win the point race!”

“My happiest moment was learning emotions aren’t ‘good’ or ‘bad’, now I don’t feel guilty when I’m angry or sad.”

“I loved the mirror game where we guessed each other’s feelings!”

“I wish I’d raised my hand more often.”

Children’s struggles are often reflections of their parents’ unresolved challenges!

The emotional problems faced by children are often a mirror of their parents’ emotions. Familial neglect, indifference and violence are always revealed through the way children behave. We noticed that a child who was very active and often disturbed others was not really sure how he should express his emotions, and could only express himself by touching others. Yet paradoxically, he exhibited extreme hypersensitivity to touch – the slightest physical contact could trigger an emotional meltdown. This contradictory response likely stemmed from frequent scolding and physical punishment at home, where touch had become associated with threat rather than comfort. It often makes us reflect: Perhaps parents need emotional intelligence training even more urgently than their children do. They must first understand their own emotional patterns before they can truly comprehend their child’s behavior.

Encouragingly, we’re also seeing parents begin to reflect and adapt. One mother questioned, “My child only focuses on homework when I nag. Surely, is there a better way to motivate them?” Another mom had an epiphany, “Why must my child always obey me? What if I listened to his perspective first?”

In my interactions with parents, I’ve observed some common struggles. Most often, it’s the mothers who drop off and pick up their children, while many fathers just focus on earning money and playing video games at home, showing little involvement in their children’s education. Meanwhile, mothers juggle demanding jobs while also supervising homework and worrying about their children’s physical and mental well-being after work. One mother even enrolled in a college program to earn an associate degree, all to accumulate enough points for a Shanghai residence permit. Without it, her child would have to return to their hometown early, adapting to a comparatively rigid and insular education system for middle and high school.

Overall, mothers demonstrate deeper concern for their children’s emotional well-being. Not only do they dominate school pick-up and drop-off duties, but they also actively engage in discussions with teachers, showing greater willingness to observe and understand their children’s evolving needs.

A special thank-you to my partner, Ariel. Her sharp judging personality trait and structured approach pushed our work to new heights. At moments when I would have settled for “good enough”, her persistence elevated our outcomes. Without her, managing the classroom would have been exponentially more challenging.

My appreciation also extends to Miki, Stepping Stones’ SEL program manager, whose teaching philosophy taught me invaluable lessons. In today’s fast-paced world, her commitment to this long-term, meaningful work is truly inspiring.

What’s more, while teaching the kids about their emotional thermometer, what a growth mindset and empathy are, I’ve also started listening to myself more. Some of the emotional solutions that work for kids are totally applicable to myself as well. In SEL’s classroom, I’m learning along with the kids and realising that exploring emotions is something that everyone needs to do and continue to do for the rest of their lives.